https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/what-is-fluxus

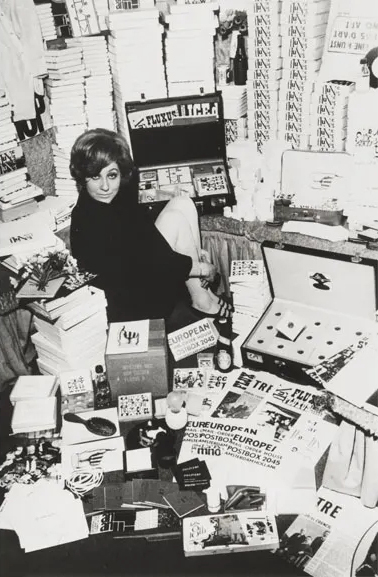

Willem de Ridder: European Mail order Warehouse Fluxshop (winter 1964-1965)

Willem de Ridder: European Mail order Warehouse Fluxshop (winter 1964-1965)

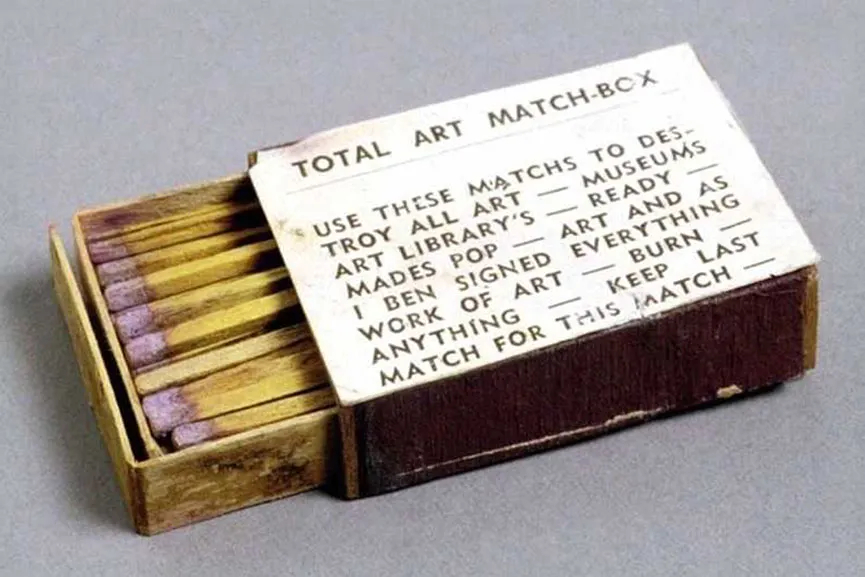

Ben Vautier: Total Art Matchbox (1966)

Ben Vautier: Total Art Matchbox (1966)

Image via fondazionebonotto.org

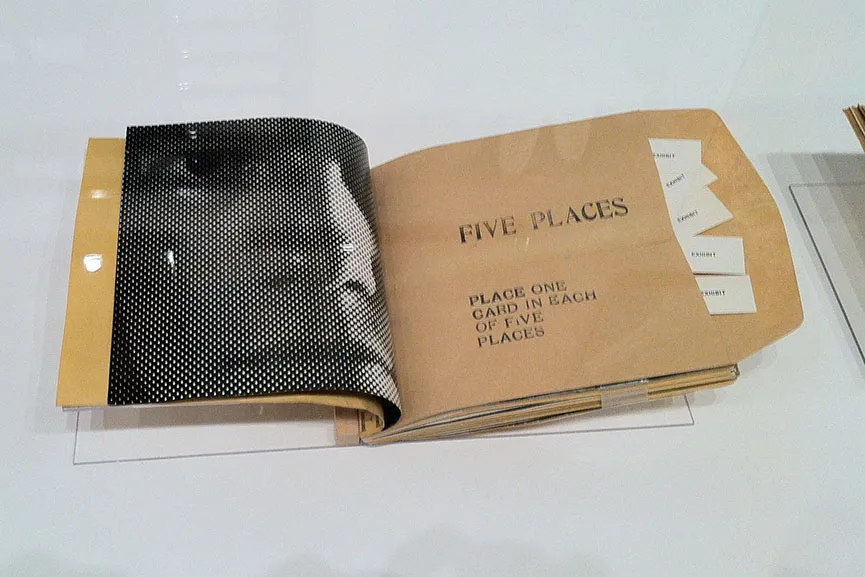

George Brecht: Five Places (1962)

George Brecht: Five Places (1962)

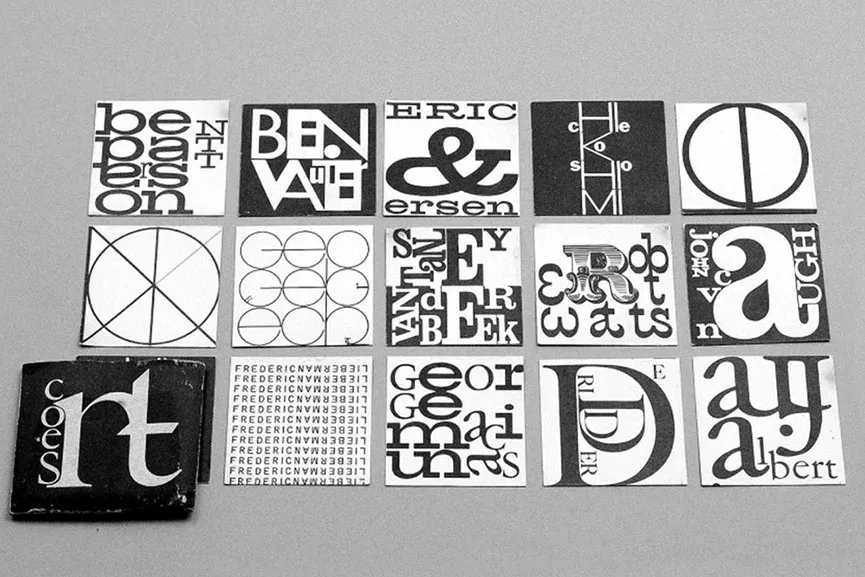

George Maciunas: Name Cards (1964)

George Maciunas: Name Cards (1964)

Nam June Paik: Werke Music Fluxus Video (1976)

Robert Filliou and Scott Hyde: Hand Show (1967)

Robert Filliou and Scott Hyde: Hand Show (1967)

Takeshia Kosugi: Anima I Ben Vautier Attaché de Ben George Maciunas Solo for Violin (Simultaneous performance, May 23rd 1964)

Takeshia Kosugi: Anima I Ben Vautier Attaché de Ben George Maciunas Solo for Violin (Simultaneous performance, May 23rd 1964)

It was the year 1961 when George Maciunas, an extravagant art historian from Lithuania, proclaimed the birth of Fluxus. It was a new group of aspiring artists gathered around John Cage, a composer who taught a series of classes in Experimental Composition at the end of the 1950s at the New School for Social Research in New York City. Following the idea of embarking on an artistic journey without having a conception of an eventual end, the group explored the indeterminacy in art and the notions of chance and infinity. Avid fans of Marcel Duchamp and Dadaism, the idea of blurring the line between everyday life and arts with a sense of humour and the urge to get away from clear definitions of what an artwork should be, imposed by museums and other cultural institutions, these artists gave their own interpretation of experimental and performance pieces. All of this made nothing less of a strong impression on said George Maciunas, who decided such actions and events should “flow” and “effluent” the entire world – and they did, for some twenty years that followed.

The Definition of Fluxus

The Fluxus movement, in all its complexity, derives from a group of individuals from a vast choice of creative disciplines and media – art, poetry, architecture, design, literature, even economics and chemistry. Strongly and proudly “anti-art”, the group consisted of names such as Al Hansen, Jackson Mac Low, Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, George Brecht, Robert Filliou, Yoko Ono, La Monte Young, Henry Flint, Wolf Wostell and the influential Gutai artists, all following the guidance of George Maciunas who is often cited as the driving force behind this innovative idea. Fluxus could be described as “open-minded”, available to anyone and everyone who was interested, constantly on the move, in the flow. Its artworks are events, actions, performances that aim to prove that life is art and art is life, that anybody could do it and that they should. It was a movement which fused many other movements, like conceptual art and minimalism, and endorsed progressive forms of expression like performance and video, encouraging the artist to focus on the process of creation, rather than having a finished product. But perhaps the best definition of Fluxus comes from its very manifesto, written by Maciunas in 1963, turning it into a proper, official movement of an international character.

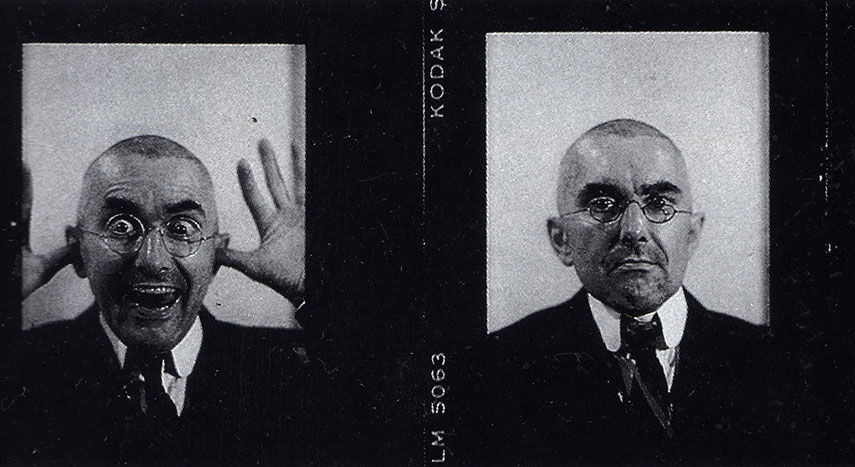

George Maciunas by Peter Moore, 1966. The art historian and enterpreneur is widely regarded as Fluxus’ founder and leading figure

George Maciunas by Peter Moore, 1966. The art historian and enterpreneur is widely regarded as Fluxus’ founder and leading figurePurging the World – George Maciunas’ Manifesto

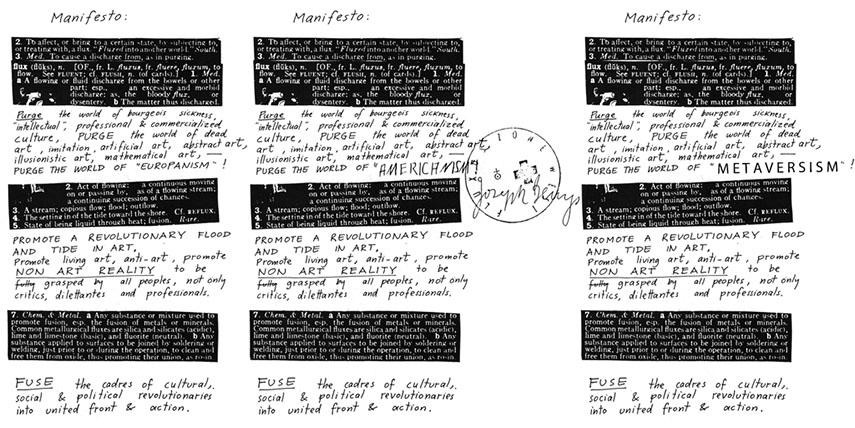

As a movement of a free spirit, one that creates a commingling between different media and techniques, as well as between art and life, Fluxus wanted to Purge the world of bourgeois sickness, “intellectual”, professional & commercialised culture”, release the art from its artificial, abstract, illusionistic and mathematical form, offering it to a public beyond critics, dilettantes and professionals. For George Maciunas and the Fluxus artists, it was about merging cultural, social and political realities into a single entity which will become the new face of action, of revolution. The Fluxus Manifesto fought against “Europeanism” and “Americanism”, putting creative tools into the hands of regular folk. And so, performances and events mixed with simple everyday gestures, such as smoking, breathing, chatting, to create unique structures, so familiar yet so brand new.

The Fluxus Manifesto, written by George Maciunas in 1963

The Fluxus Manifesto, written by George Maciunas in 1963

Fluxus and Art – Event Scores, Performance and Fluxkits

Following an ideology coined by Dadaism and inherited by Neo-Dadaism, Fluxus kept its urge to be anti-commercialist, divorcing its own artworks from market-driven tendencies. Because anything could and should be art, the artists used whatever materials they had at hand, often in collaboration with other Fluxus artists. However, inspired by Duchamp’s ready-mades, George Maciunas assembled many of the Fluxus multiples, books and editions, meant for mass production. These were often signed, numbered and coming in limited editions, intended for sale at high prices. While these publications were perhaps the most numerous objects from the artists’ rich oeuvre, today it is the event scores and the famous Fluxus boxes that are associated with the movement the most.

Fluxus introduced the event scores as the scripts for performance pieces, while the Fluxkits became versatile collectable items.

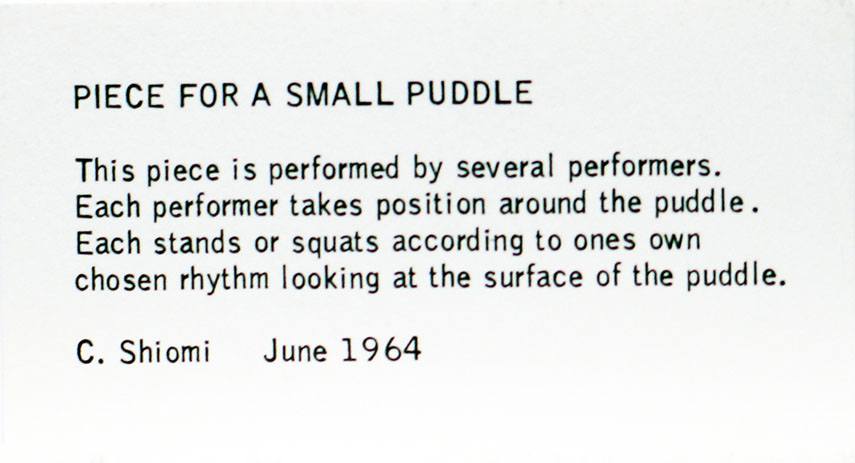

Often compared to Happenings, the Event Scores were influenced by avant-garde music, staying true to the original group gathered around John Cage – in fact, many of the artists who successfully produced event scores attended Cage’s courses. While Happenings were longer and more complex, Fluxus’ events often consisted of few lines only, describing actions that are to be performed. Some of the most iconic pieces include George Brecht’s Drip Music and Alison Knowles’ instructions to “make a salad” or “make a soup” from the 1960s. As we can presume from their characteristics, the event scores were meant to frustrate the high culture of academics in art and to elevate the banal and the mundane to a higher level of appreciation.

On the other hand, the Fluxkits, or Fluxus boxes, were introduced by, you’ll guess, George Maciunas. Marketed through the mail, these were collections of objects made by other artists, ranging from graphical scores for events, interactive boxes and games, print cards, journals, films. This project was inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise, and was conceived as a collective product. Enclosed in plastic or wooden boxes, Fluxkits also ranged in prices, from one to a hundred dollars, depending on the amount of objects they would enclose.

Fluxus was also instrumental in the promotion of forms like performance art, unconventional sculpture, experimental music of course, and video-making. Among the most important artworks of the 1960s and 1970s, the movement’s most fruitful decades, we have Yoko Ono’s iconic Cut Piece, which put the artist at the mercy of the audience and is still considered a seminal feminist art piece; Nam June Paik’s Zen for Film, which stands as a perfect example of the irony embraced and expressed by Fluxus.

Fluxus Artist Alison Knowles Discusses the Fluxkits

What is Intermedia ?

Another important aspect of Fluxus is Intermedia, a term used by Hannah and Dick Higgins to describe and emphasize various interdisciplinary activities that came as a result of collaborations between different artistic genres. According to the artists, an artwork placed between two or more media holds an immense value, and it is much more appreciated than an artwork deriving from a single technique. Indeed, the pieces produced by the Fluxus group often married areas such as music and philosophy, like in the works of John Cage and Philip Corner, or poetry and sculpture, evoked by Robert Filliou’s pieces. Intermedia rejected Modernism and its urge to categorise artworks and specialise artists, paving the way to the experimental forms used in contemporary art today, through myriad forms of new media.

Mieko Shiomi: Piece for a Small Puddle from Events and Games (1964. Fluxus Edition announced 1963)

Mieko Shiomi: Piece for a Small Puddle from Events and Games (1964. Fluxus Edition announced 1963)

The Museum of Modern Art. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift. © 2011 Mieko Shiomi

Fluxus is Dead, Long Live Fluxus

What started with George Maciunas, ended with George Maciunas. The founder and leader of the movement died in 1978, symbolically marking the end of Fluxus as such. It was turned into an event of a kind, entitled Fluxfeast and Wake, where foods that were only black, white or purple were served. In decades to follow, the original artists continued their work, although many argued that it could no longer be considered Fluxus. The movement’s ideology inspired the creation of a vibrant post-Fluxus community of writers, musicians and performers which emerged with the rise of the Internet in the 1990s, and can be recognized in today’s multi-media digital art performances, for instance – as well as Land art and, of course, graffiti and street art. As long as there are artists who deliberately work outside established museum systems, Fluxus can successfully claim its influence and will continue to live on as it was always intended to – through many, many media, accessible to anyone.

Editors’ Tip: Fluxus Experience

Written by Hannah Higgings, who was in the centre of it all, this groundbreaking work of incisive scholarship and analysis explores the influential art movement Fluxus. Higgins examines these two setups to bring to life the whole experience, how it works, and how and why it’s important. She does so by moving out from the art itself in what she describes as a series of concentric circles: to the artists who create the works, to the creative movements related to it (and critics’ and curators’ perceptions and reception of them), to the lessons of its art for pedagogy in general. The author, the daughter of the Fluxus artists Alison Knowles and Dick Higgins, makes the most of her personal connection to the movement by sharing her firsthand experience, bringing an astounding immediacy to her writing and a palpable commitment to shedding light on what Fluxus is and why it matters.

Featured image: Takeshia Kosugi – Anima I & Ben Vautier, Attaché de Ben & George Maciunas, Solo for Violin. Simultaneous performance, May 23rd 1964, by Ben Vautier and Alison Knowles (not pictured) during “Fluxus Street Theatre” as part of “Fluxus Festival at Fauxhall” New York City. Photography by George Maciunas. 51 x 40.5 cm; Ben Vautier – Total Art Matchbox, 1966; George Brecht – Five Places, 1962; George Maciunas – Name Cards, 1964; Left: Nam June Paik sitting in TV Chair (1968/1976) in Nam June Paik Werke, 1946–1976: Music,Fluxus, Video, 1976. © Friedrich Rosenstiel, Cologne / Right: Willem de Ridder – European Mail-order Warehouse/Fluxshop, Winter 1964–65. Photo by Wim van der Linden/MAI. The Museum of Modern Art. Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift; Robert Filliou and Scott Hyde – Hand Show, 1967. All images used for illustrative purposes only.

Angie Kordic

May 11, 2016