http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/4562132.stm

Last Updated: Tuesday, 27 December 2005, 11:57 GMT

The Beano comic character Billy Whizz famously runs so fast that he doesn’t get wet in the rain. Is this possible? Inspired by BBC Online Magazine’s occasional Formula Won feature, which highlights equations of dubious value, here’s a brief analysis of the problem.

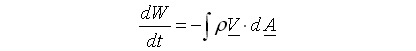

The formal solution looks something like this:

Which looks a bit (Dennis the) menacing. dW/dt is the rate you’re getting wet (mass of rain per time incident on your body.) ρ is the density of the rain shower (mass of water in unit volume of atmosphere.) V is the velocity of the rain relative to you, and dA represents a little bit of your body surface. The large „S” shape tells you to add together all the rain falling on these little bits of body surface to calculate the total amount of wetness per time. (Picky note: the summation should only be done over body surfaces facing the rain, or the equation will accidentally calculate „negative” rain that it thinks has passed right through your body.)

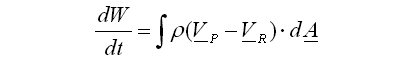

The relative velocity of the rain depends on the rain’s velocity, and your own velocity. This is where we can introduce the possibility of someone running around in the rain. The relative rain velocity, V, is equal to the true velocity of the rain minus the velocity of your body. We can now put these in the above equation and write:

Where VP is the velocity of the person and VR the velocity of the rain. (They’re not the wrong way round, because we dropped the minus sign.)

Precisely! The problem with a solution like this, is that although it is designed to be exactly correct, it is far too complicated to be of much use – because it can’t easily be calculated.

For a start, the shape of a human body is too complex, and all parts of it are in different states of motion when running. To get some answers the formal solution must be simplified by making some assumptions and approximations. Physicists do this all the time – it is called „cheating”.

This is where the fun starts. To get some idea of how running around in the rain affects wetness, we’ll need to make some fairly significant simplifications.

We will assume that the rain is falling vertically and also that the person is running horizontally. To get around the problem of our complex body shape, we’ll imagine our person as a rectangular block – like a house brick standing on end. The smaller top surface of this „brick” is of area a and represents all our own top surfaces (head and shoulders.) The larger front surface of this brick is of area A and represents our front surfaces (chest, stomach, front of arms, front of legs etc.) This approximation won’t give us the complete truth – but it might provide some insight into what is going on.

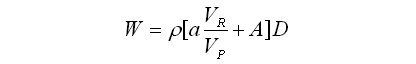

This enables us to produce our first „total wetness” equation. It can be derived from the formal solution above, or worked out by other reasoning. Anyway, here goes:

Here W is the „total wetness” (the total mass of rainwater on your body), ρ is the rain shower density as before, a our top surface area and A our front surface area. VR and VP are the velocities of the rain and person respectively and t is the time spent out in the rain.

Looking at the equation, it’s clear that there is little we can do about the rain velocity, rain density and the size of our bodies (except by dieting.) The only quantities we can directly control in the total wetness equation are t (the time spent in the rain) and VP (how fast we’re running.)

The equation tells us quite clearly that we get most wet if we:

1) stay out in the rain for a long time (no surprise there)

and / or

2) run very fast

So running fast actually makes us wetter according to this analysis – the reason being that you are moving your front surface through the „rain field”, scooping up water as you go.

By the way, should you ever want to get really wet, the equation suggests you should stay out in the rain for a long time whilst running around like a maniac.

There’s more to it than this though. Although running fast looks like a bad idea, what if we are running towards shelter – surely by running we will minimise the time spent in the rain? This is a fair point, and makes the first equation look incorrect – but in fact it is fine.

This is because the equation „knows” nothing about the possibility of shelter. It simply tells us that if you’re in the rain, the best thing to do is stand still. However, we can introduce the idea of shelter into it to get some further advice.

Let’s assume that when it starts to rain, you identify the nearest shelter and run towards it. If the distance to the shelter is D, then the time spent in the rain (t in the above equation) will be D/VP.

If we insert this into the „total wetness” equation to replace t, we get the „modified simplified total wetness equation” which now includes the distance to the shelter D:

So here we have it – more mathematical advice to avoid getting wet. Because we divide by VP in this equation, maximising our velocity now emerges as a good idea, assuming there is a shelter available.

When it starts to rain, first identify the nearest shelter, and then run to it as quickly as you can.

This is remarkable, because that is precisely what most people do! The power of mathematics has finally given us the reassurance that, when we run for that bus shelter, store canopy or random shop (and start pretending to browse), we are getting it exactly right!

Bad news for Billy Whizz though – the equation shows that you get wet no matter how fast you run, with a minimum value of W = ρAD.

PS: If the rain is falling at an angle it is possible to decrease your total wetness by running in the correct direction. Unfortunately this may not coincide with the nearest shelter direction. If you are worried about this, we may be able to deal with it in a further instalment.

PPS: Alternatively, ignore the maths and get an umbrella.

Nick Allen is a Master of Science in astrophysics and a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society. An entrepreneur and inventor, he was also co-developer of MouseCage, a disability software www.mousecage.org. Nick continues to teach physics to advanced students at Valentine’s High School, Ilford.